Military courts were established to try “jet black terrorists” in January 2015 as part of the National Action Plan – just a month after the deadly terrorist rampage at the Army Public School in Peshawar. The aim was to ensure swift and expeditious justice in terrorism cases. The courts were set up through a constitutional amendment with a “sunset clause” for a period of two years, but their tenure was extended for another two years in 2017. Now, with another extension being debated, The Express Tribune explains what the military courts are, how they work, and why they divide opinions

It was December 2007. A woman was murdered in Rawalpindi. Her case dragged on for a decade. Prosecutors change, judges change, even the suspect list keeps changing, but ten years later, a court finally decided on the case. All five prime suspects were released for want of evidence.

The woman was among two dozen people who died that fateful day in Rawalpindi, but her name stands out on the list of victims – Benazir Bhutto.

The case of the former prime minister is just one of the unfortunately high number of so-called "classic examples" of the failure of the Pakistani criminal justice system (CJS). Indeed, it was because of this sorry history that through a constitutional amendment in January 2015 – weeks after the APS Peshawar attack – Pakistan established military courts to try accused terrorists. The new law had a sunset clause of two years, but the courts have since been given two extensions. That is because today, four years after their inception as a stop-gap arrangement the federal and provincial governments have woefully failed to take any steps to make the criminal justice system more effective.

The Police Reforms Committee (PRC) constituted by the Supreme Court has comprehensively discussed the effectiveness of CJS and terrorism cases.

The committee was headed by former inspector general of Sindh Police (IG) Afzal Ali Shigri and comprised former Punjab IG Syed Masood Shah, former Sindh IG Asad Jahangir Khan, former Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) Director General (DG) Tariq Khosa, former Sindh IG Shoaib Suddle, and all incumbent inspectors general spent seven months preparing a report on police reforms, while also diagnosing weak areas in CJS regarding terrorism cases, provide a roadmap to enhance the effectiveness of the CJS for dealing with terrorism cases, evaluating existing laws for their efficacy, and recommending measures to effectively combat terrorism and violent extremism. The Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan, led by then-chief justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar, on January 14 conducted a ceremony to launch the PRC report.

To terminate or adjudicate?

The PRC says that there are two models to deal with the challenge of terrorism – the war model and the criminal justice model. In the war model, the military plays the lead role and follows the rules of war in dealing with terrorists and terrorism affected areas. In the criminal justice model, the police play the lead role and the criminal justice system is the main instrument to deal with terrorists.

In Pakistan, the war model is being followed in insurgency-hit areas – such as those straddling the Afghan border – and the criminal justice model to deal with terrorism in the rest of the country.

The PRC report states that there is hardly any study that analyses national-level data to diagnose what ails the CJS in general and the anti-terrorism regime in particular. Without such data, it is near-impossible to make holistic recommendations. There have, however, been a few studies carried out at the provincial level.

Provincial research

The PRC report reveals that a study was carried out in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa for the years 2015, 2016, and 2017 indicated that, on average, 48 per cent of cases filed by the police under the Anti Terrorism Act (ATA) and sent to the Anti-Terrorist Courts (ATCs) were eventually discharged or dismissed by the courts.

Another study highlighted some of the deficiencies of the investigating officers posted in the K-P Counter Terrorism Department (CTD). Most of the investigation officers (IO) posted in the K-P CTD had not received any specialised training in dealing with terrorism investigations of cases, indicating a serious gap in police training programmes in K-P.

Moreover, an overwhelming number of IOs were not even aware of the investigation-related provisions of the Fair Trial Act, which prescribes the legal procedure for IOs to wiretap and intercept terrorists' communications in a manner that the information is admissible in court.

Another study was carried out by a police officer to identify the reasons for acquittal in terrorism cases in Punjab between 1990 and 2009. The study analysed 178 acquittal judgments and broadly identified three reasons – defects in the FIR, flawed investigations, and prosecution problems.

A similar study carried out by another police officer on cases registered under the ATA in Punjab points out the frequent application of ATA to crimes such as gang rape, and mass murder, which, strictly speaking, do not usually fulfil the definition of terrorism.

In fact, the study highlighted that between 2005 and 2011, only 4.6 per cent of cases registered under the ATA in Punjab involved explosives or suicide bombers, the most recognisable form of terrorism.

The same research also indicated that the average conviction rate in ATA cases in Punjab courts during the same period was only 14 per cent.

The PRC notes that after the CJP formed it to give recommendations to the Law and Justice Commission for Police Reforms, a quick survey was conducted. The provincial CTDs were asked to share the latest conviction figures in terrorism cases. It was found that the conviction rate improved in Punjab, going up to 61 per cent in 2016 and 2017, while in K-P it was just 30 per cent, and in Sindh it had gone down to an abysmally low four per cent.

The commission notes that there needs to be a significant improvement in the conviction rate in all the provinces, while also calling on Punjab to share the best practices employed to improve its conviction rate.

Reviewing anti-terrorism laws

ATA reforms

The basic law to combat terrorism is the ATA. The PRC report reveals that the loose definitions of "terrorism" and "terrorist act" have resulted in considerable ambiguity as well as the application of the act, in many cases where it should not have been applied. Murder and attempted murder, which can and should ordinarily be covered by the general criminal law under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), have been registered under the ATA whenever some sensationalism has been attached to the surrounding circumstances. This is possible only because of the loose wording in the Act.

Another problem is that in many cases, an ATA clause is added to a murder charge appears at the request of complainants or the police to ensure a higher legal sanction and more severe punishment. New categories of offences, such as acid attacks and kidnapping for ransom have also added to the act because of demands for stricter penalties for these offences.

The report recommends that there is a need to revise the Act to directly address new categories of crimes, include suicide bombings and attacks, conspiracy to commit such attacks, armed insurgency, and conspiring to cause widespread disaffection against the state.

In addition, the definitions of 'terrorism' and 'terrorist act' also need to be improved so that any attacks attempting to or resulting in large scale destruction or widespread damage can be included.

Further, a special section on 'weapons of mass destruction' needs to be introduced along the lines of US laws, which define such attacks in a separate category to reinforce both, their different nature and the gravity of their consequences.

A special category of offences for attacks on security installations, armed forces, and law enforcement agencies and their facilities should be created, along with one for highly sensitive installations or infrastructure. Any symbol of national importance should be included in this category. The report explains that the attacks on the Sri Lankan cricket team, GHQ, PNS Mehran, Sargodha Police Academy, and the FIA building underscore the importance of separate categories.

Meanwhile, recoveries of explosives and weapons are covered under the Explosives Act, 1884, the Explosive Substances Act, 1908, and the Pakistan Arms Ordinance, 1965, and are not offences under the ATA.

This practically means that illegal weapons possession, even high calibre or automatic weapons, is only punishable with short jail terms and modest fines. Historically, courts have even been reluctant in awarding these punishments, and this tradition carries over even into cases that are registered under ATA. Therefore, possession of arms in relation to terrorist acts does not result in penalties to match the crime. Similarly, the Explosive Substances Act is an antiquated law that does not adequately apply to modern explosives.

Aiding and abetting terrorism

The PRC believes that terrorist acts, in their modern form, require the active collaboration and assistance of several people to succeed. However, the act fails to sufficiently take into account recruitment and radicalisation, terror financing, and other forms of aiding and abetting terrorism.

Training suicide bombers, bomb-making training, weapons training, and harbouring terrorists are some examples of aiding and abetting. Similarly, propagation and dissemination of ideas or literature leading to terrorism should also attract more serious penalties.

There is also no provision for providing assistance within Pakistan to any international agencies in connection with acts of international terrorism with links in Pakistan. A provision needs to be made with a prescribed mechanism for such assistance. The report also criticises the limited attention paid to terror financing.

Law enforcement

The PRC notes that law enforcement agencies and courts are hampered in effective investigations and adjudication of cases due to lack of legal powers which are necessitated by the very nature of terrorism in recent years and rapid changes in technology.

There is a need to provide powers to the police and other investigating agencies such as the FIA and provincial CTDs for the monitoring and surveillance of persons, financial transactions and money flows in connection with terrorism. It also suggests looping in financial institutions.

The report further states that there is a need for an effective victim and witness protection program under the act, instead of the status quo position of leaving it to the provinces. The police and the courts should also be empowered to "take all necessary steps" to ensure that the victims, witnesses, judges, investigation officers and prosecutors are effectively protected in during and after terrorism trials. These steps could involve image and voice distortion, closed sessions, and any other measures considered necessary and expedient in the interest of justice and the protection of witnesses.

Procedural issues

Procedural bottlenecks effectively kill any chances of successful prosecution and conviction in terrorism cases. The report calls the provisions in the law of evidence and court rules "antiquated" and says they do not cater to the new reality of the present day. There is a need to amend the law of evidence as well as the act to make the testimony of police officers admissible as evidence, which is already the case in many countries around the world, especially in the context of terrorism cases, where witnesses are not forthcoming due to fear and oral testimony is given significant value. This would require amendments are needed in the law of evidence, specifically in the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order, along with amendments in the act itself.

Further, there is a need to amend the law in order to make circumstantial evidence admissible in terrorism cases, but only after building safeguards into the act to ensure that it is not misused.

The report states that there is a need to come up with a mechanism to do away with the requirement of physical presence at the crime scene. There is also a need to move away from the approach of connecting the persons present at the scene of a crime to the persons planning the terrorist act. In such circumstances, the standard of proof required in the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order should be relaxed and circumstantial evidence should be made admissible.

Similarly, it is also stated that the premier strategic-level national body for counterterrorism is the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA), established under the NACTA Act, 2013. Some of the important provisions of the NACTA Act are not being implemented.

The law clearly lays down that the organisation shall be responsible to the prime minister, yet the Interior Ministry refuses to let go of it. As per the law, an essential starting point of NACTA has to be a meeting of the Board of Governors, headed by the PM.

The Board of Governors (BoG), inter alia, has to approve its budget, issue guidelines, and approve SOPs, but that is not being done.

Its main functions also include preparing terrorist threat assessments for the government by collating intelligence from all agencies, develop CT strategies and monitor its implementation, carry out research in terrorism-related areas, and evaluation of terrorism-related laws. But the BoG went five years without a meeting, leaving it unable to give any strategic direction or unity to the national counterterrorism effort.

Need for a federal CTD

Implementation of PRC report

Military courts and the CJP

Bar perspective

International jurists

A way forward

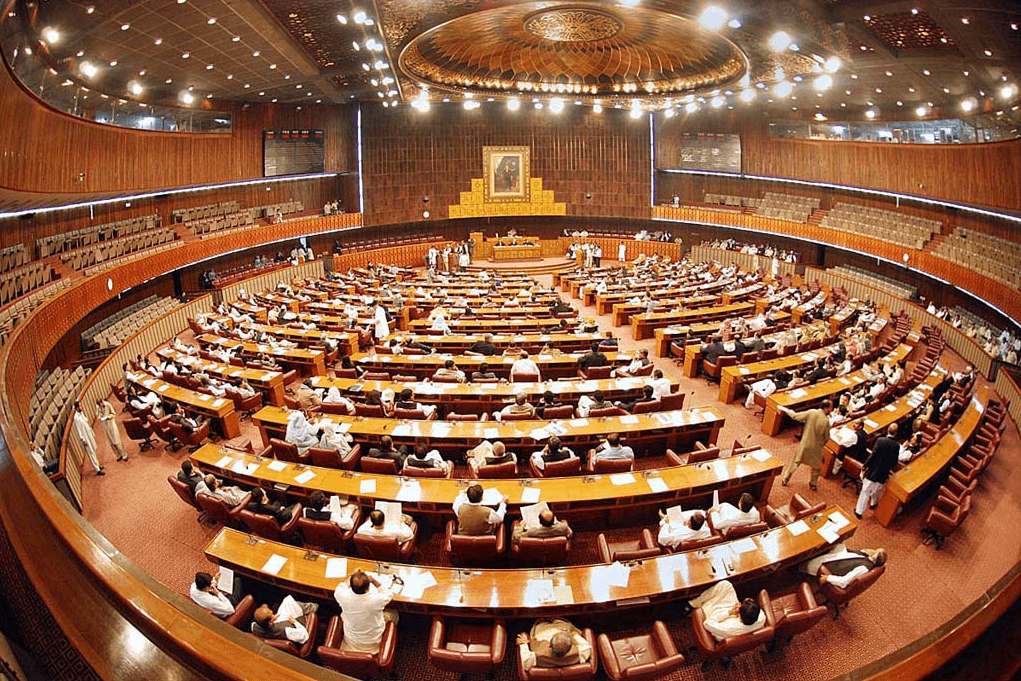

On Dec 16, 2014, Taliban terrorists rampaged through a military-run school in Peshawar. Nearly 150 people – most of them schoolchildren and some of them as young as five years of age – were massacred. It was "the most unkindest cut of all" in Pakistan's long, bloody tryst with terrorism. Revenge became the rallying call. And all political parties developed a rare consensus on the National Action Plan, or NAP, to stamp out terrorism. The extraordinary circumstances warranted extraordinary measures, so, NAP envisaged, among other things, the establishment of military courts to try civilians accused of terrorism-related offences.

Military courts were set up through the Pakistan Army (Amendment) Act, 2015 and further extended for two years through Pakistan Army (Amendment) Act 2017, by parliament on January 7, 2015 and March 31, 2017, respectively. These special tribunals are completing their mandated two-year tenure next month. If denied an extension, they would cease to function in March. Some opposition parties, the PPP in particular, say they had reluctantly acquiesced to the establishment of military courts in "extraordinary circumstances" and would not vote for a second extension because incidents of terrorism have already significantly declined in the country. The PPP fears that further extensions in the military courts' tenure might lead to "militarisation of the judiciary and judicialisation of the military".

There is no denying that the military courts were set up as a stop-gap arrangement to offer parliament time to strengthen the criminal justice system, according to proponents. They say that lacunae in the criminal justice system help terrorists get away with their heinous crimes. And expeditious trial and sentencing of terrorists would serve as deterrence. Critics, however, say the military courts are in conflict with the fundamental rights guaranteed in the 1973 Constitution. And they have their own arguments.

Controversy aside, let's see how a military court works.

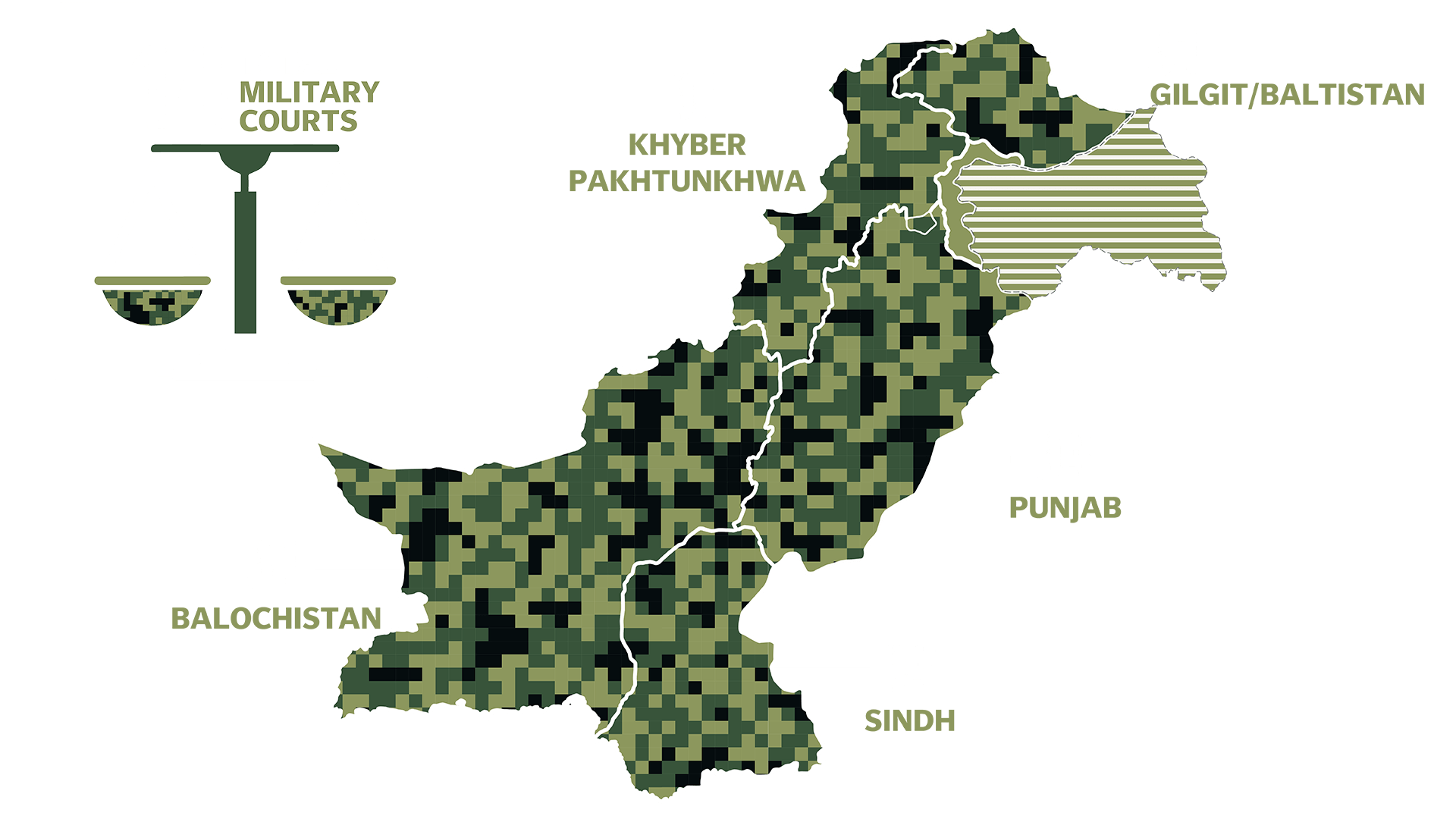

We have 14 military courts across the country – six in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, three each in Punjab and Sindh, and one each in Balochistan and Gilgit-Baltistan. Since their establishment, 717 cases had been referred to the military courts. Of these, they have adjudicated 646 cases to date. They have condemned 345 terrorists to death, of whom 56 have been hanged. Similarly, 296 terrorists have been awarded varying jail-terms, while five suspects have been acquitted due to lack of sufficient incriminating evidence.

The offences for which convictions have been granted include the killing of innocent civilians, attacking military and law enforcement officials, attacks on educational institutions, places of worship, hospitals, and airports, kidnapping, and sectarian violence, along with weapons possession and providing or receiving funding for terror activities.

So how do cases get to the military courts?

The government has a comprehensive procedure in place for transfers of terrorism cases to military courts. The transfer is approved by the federal and provincial apex committees set up to overse the implementation of NAP. Senior civil and military officials sit on these committees and decide on the merits or demerits of whether or not to transfer specific cases.

Based on their recommendations, the transfers must then be approved by the prime minister.

All approved cases are processed under the Army Act and related military rules and regulations. During the pre-trial stage, initial investigations and interrogation are carried out by police officials, usually investigation officers. Confessional statements are then recorded before a judicial magistrate under Section 164 of CrPC. A proper statement of evidence is then recorded under Army Act Rule 13. The Complete record is then vetted, first by the Corps legal cell and finally by the Judge Advocate General's Department – the army's legal arm. Charges are then framed.

At the trial stage, a court is constituted under Army Act Section 87, and convening orders for the trial are issued, with neutral officers assigned to hold the trials. Prosecution witnesses are produced before the court and evidence is recorded under Qanoon-e-Shahadat, 1984 – the Evidence Act. The accused and his lawyer are provided with a proper opportunity to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. At the conclusion of the prosecution's arguments, the defence presents its case. The accused also has the option to make any statement before the court and to call defence witnesses.

The court then deliberates and rules on the basis of all the evidence and arguments from both sides.

After the trial, the proceedings are forwarded to JAG's department for review. If approved, JAG's department then confirms the findings of the court and in case of death penalty cases, the sentence is confirmed by the COAS. The sentence of the Field General Court Martial is the promulgated to the accused, who is then shifted to a civilian jail.

The sentence can be appealed first in a military court of appeal, which is presided by a general and two brigadiers. Convicts awarded capital punishment may appeal against the sentence within 40 days of the signing of the sentence. The convict may also hire defence counsel of their own choice. The appeal court may accept or reject the appeal in whole or in part, substitute the sentence, order a retrial, annul the proceedings, or remit the sentence.

If the verdict is upheld on appeal, the convict may send a mercy petition to the COAS within 60 days of the appeals court decision, and to the president of Pakistan within 90 days of rejection of a mercy petition by the COAS.

In some instances, cases have been filled in different civilian courts against the decisions of military courts. In such cases, an accused who is unable to engage or afford counsel of his choice is provided with a public defender.

With a decision on the extension of the military courts looming, political parties have formed a mostly-united front on the issue. No more courts, they say. But their approach to getting their demands met shows fractures.

The military courts' were activated a month after the December 2014 APS attack. Their initial tenure of two years was then extended for another two.

Four years on, party leaders see the courts' future in a different light. Senior Pakistan People's Party's leader and the country's former prime minister Syed Yousuf Raza Gillani says the courts were only meant to be in place for a short time and could no longer be afforded. Besides Gillani, senior PPP leader Farhatullah Babar also expressed serious reservations about extending their tenure.

Meanwhile, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) says the decision is up to the parliament, and that it is developing a consensus. Federal Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry says the courts, part of the National Action Plan, were established in a different political climate and an alternate mechanism would be put in place if they were removed. "These courts were established and later extended by the parliament. Their purpose was to eradicate militancy," PTI's KP spokesperson Shaukat Yousafzai says in support. In a similar vein, Jamaat-e-Islami Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan agrees the courts were established "in a state of helplessness," so that parties were "compelled" to accept them, adding that parliament never reformed the civil judicial system as it should have.

JUI-F Senator Hafiz Hamdullah mentioned his disdain over the courts, saying the National Accountability Bureau, Joint Investigation Teams have now been "militarised", and the apex court is now under pressure. The party was never in favor of the courts, the senator says. "If the apex court can handle Mumtaz Qadir's high profile case and at the same time let Asia Masih go free, why can't it decide militants' cases?" The civil judicial system deserves attention and reform, the senator says.

As political parties deliberate, PTI faces serious pressure. Pakistan People's Party senior leader Makhdoom Ahmed met PML-N's jailed Nawaz Sharif in Kot Lakhpat Jail. Sources say PPP, PML-N, JUI-F, including other opposition parties, are all set to oppose the extensions. They also plan on demanding the government report on the courts' performance and justify their continued existence. Various party leaders have also formed a committee which includes PML-N's Rana Sanaullah, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, Ahsan Iqbal, Rana Tanveer, PPP's Raja Pervaiz Ashraf, Khursheed Shah, Naveed Qamar and Senator Sherry Rehman, JUI-F's Maulana Abdul Wassay, ANP's Amir Haider Khan Hooti and JI's Alia Kamran. This committee will hold talks with the government's own committee which includes Defence Minister Pervaiz Khattak and Minister of Education Shafqat Mehmood.

And though the government hasn't yet extended an invitation for talks on the matter, Defence Minister Pervaiz Khattak invited opposition leader Shehbaz Sharif for a meeting in National Assembly Speaker Asad Qaiser's chamber. The invitation was turned down by Sharif. Sources say he isn't ready to talk to the party leadership on the matter, even as other parties have consolidated their stance. The party has reportedly also banned members from giving policy statements on the issue.

Expeditious trials and the judicial system's incapacity to deliver speedy justice make an argument for the extension of the military courts. But the buck stops at the fairness of the trial. Is the country's persistent reliance on military courts - and the opacity of the legal process in these tribunals - counter-productive for Pakistan's anti-terrorism efforts?

"Justice should not simply be 'speedy' - it should also be carried out through a just, legally correct, fair and open trial process. Justice must not only be done - but it must also be seen to be done," stressed human rights activist Tahira Abdullah.

General (retd) Amjad Shoaib explained that the idea behind speedy trials at military courts revolved around discipline. "A system has been developed to ensure people are held responsible without delay. As a backbone of the armed forces, it is imperative to maintain discipline."

On the other hand, defence analyst Imtiaz Gul dismissed the idea that military courts provided quick justice. "Statistics show that over 700 cases have been forwarded to military courts since 2015. Out of which 500 were decided. But the precise statistics show that only 18 per cent of the sentences were carried out. The remaining 82 per cent are pending appeals with apex and high courts. It shows that the military courts have been unable to execute convictions."

Shoaib argued that the military courts conducting trials of civilians did not qualify as 'pure' military trials conducted by the army. "The convicts are allowed to file appeals in civil courts where cases are dragged. The intelligence gathered by agencies is dismissed in civil courts. The convicts are then acquitted."

Abdullah said military courts were not a solution as they violated basic human rights and fundamental constitutional requirements of the right to a fair trial. "It is neither a short-term nor a long-term viable solution."

Reiterating that military courts are not a permanent solution, Nasir claimed that it allowed "matters to be covered up" hence proving counter-productive for the country's counter-terrorism narrative.

Lieutenant-General (retd) Talat Masood believes the military courts were an interim arrangement to cater to a huge backlog of cases piled up over the years.

Masood reflected that the military courts were also meant to create an image that the state is determined to punish terrorists. "It was expected that the government would take remedial measures to overcome the shortcomings and revert to the dispensation of cases through civilian courts."

He said since successive governments had failed to derive a mechanism, another extension for the military courts has become inevitable. He added that the arrangement could not continue indefinitely.

Abdullah asserted that no number of extensions can enforce judicial restructure or reduce the backlog of pending cases. "The reforms must come from the judiciary itself with genuine support from the executive branch. Filling the vacant positions at all tiers, police reforms to improve criminal justice administration are important."

Gul stressed that the long-term solution lies with the revision of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPc) and the Civil Procedure Code (CPc). "These laws are from the 1860s British era – in the United Kingdom, the laws are revised every 15 to 20 years."

List of convicts awarded death sentence by military courts to date

| Ser | Name | Press Release no and Date | Death Sentences | Rigorous Imprisonment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Noor Saeed, Haider ali, Murad Khan, Inayatullah, Israr uddin and Qari Zahir and Abbas | 79/2 Apr 15 | 7 | 1 |

| 2. | Civilian Muhammad Sabir Shah alias IkramUllah S/O SherHazrat, Civilian Hafiz Muhammad Usman alias Abbas alias Asad S/O Ali Dost, Civilian Asad Ali alias Bhai Jan, Civilian Tahir S/O Mir Shah Jahan, Civilian Fateh Khan S/O Mukaram Khan and Civilian QariAmeen Shah aliasAmeen S/O Minar Shah | 274/2 Sep 15 | 7 | 1 |

| 3. | Civilian Hazrat Ali S/O Awal Baz, Civilian Mujeeb ur Rehman alias Ali alias NajeebUllah S/O Ghulab Jan, Civilian SabeelalisasYahya S/O Atta Ullah, Civilian MolviAbdus Salam S/O Shamshi, Civilian Taj Muhammad alias Rizwan S/O Altaf Khan, Civilian Ateeq ur Rehman alias Usman S/O Ali Rehman, Civilian Kifayat Ullah alias Kaif Qari S/O Ghulam Haider (RI) and Civilian Muhammad Farhan alias Ali alias Abbas alias Aijaz Qadri | 246/13 Aug 15 | 7 | 1 |

| 4. | Civilian Said Zaman Khan S/O Said Nawaz Khan, Civilian Obaid Ullah S/O Muhammad Azam Baloch, Civilian Mehmood S/O Khawaza Khan, Civilian Qari Zubair Muhammad S/O Sakhi Muhammad, Civilian Rab Nawaz S/O Shahi Room, Civilian Muhammad Sohail S/o Zahoor Ahmed, Civilian Muhammad Imran S/O Muhammad Hanif, Civilian Aslam Khan S/O Rozi Khan, Civilian Jameel ur Rehman S/O Sher Rehman and Civilian Jamshed Raza S/O Allah Ditta (RI) | 291/21 Sep 15 | 9 | 1 |

| 5. | Muhammad Ghauri S/O Javed Iqbal, Muhammad Imran S/O Abdul Manan, Aksan Mehboob S/O Asghar Ali and Adbul Rauf Gujjar S/O Rehmat Ali (accused no 1), Muhammad Hashim S/O Muhammad Abdullah (accused no 2) ,Sulaman S/O Boneer ( accused no 3), Shafqat Farooqi S/O Malik Liaqat Ali (accused no 4) and Muhammad Farhan S/O Muhammad Rafique (accused no 5) | 1/1 Jan 16 | 9 | 0 |

| 6. | Muhammad Arbi S/O Hafiz Muhammad Sadiq, Rafi Ullah S/O Muhammad Miskeen, Qari Asif MehmoodS/O Muhammad Anwar, Shawaleh S/O Gul Khan, Muhammad Zeeshan S/O Abdul Qayyum Khan, Nasir Khan S/O Khan Afsar Khan, Shoukat Ali S/O Abdul Jabbar, ImdadUllah S/O Abdul Wajid, Muhammad Umar S/O Saida Jan, Sabir Shah S/O Syed Ahmed Shah, Khandan S/O Dost Muhammad Khan and Anwar Ali S/O Fazal Ghani | 51/11 Feb 16 | 12 | 0 |

| 7. | Irfan Ullah S/O Khudayar, Mushtaq Ahmed S/O Muhammad Miraj, Muhammad Nawaz S/O Gul Muhammad, Taj Gul S/O Sultan Zareen, Asghar Khan S/O Aziz Ur Rehman (Convict Number 1), Ahmed Ali S/O Bakhat Karam (Convict Number 2) and Haroon ur Rasheed S/O Mian Said Usman (Convict Number 3), Bakht-e-Ameer S/O Ameer Zareen, Aziz Khan S/O Ashber, Fazal-e-Ghaffar S/O Shehzada, Asghar Khan S/O Ahmad Jan, Ikram Ullah S/O Habib Ullah and Haider S/O Daim Khan | 88/15 Mar 16 | 14 | 0 |

| 8. | Muhammad Umar S/O Daleel Khan, Hameedullah S/O Muhammad Ghazi (Convict Number 1), Rehmatullah S/O Umar Din (Convict Number 2), Muhammad Nabi S/O Dilawar Shah (Convict Number 3) and Moulvi Dilbar Khan S/O Kashkar (Convict Number 4), Rizwan Ullah S/O Taj Mir Khan, Gul Rehman S/O Zareen, Muhammad Ibrahim S/O Maseen, Sardar Ali S/O Muhammad Akram Khan, Sher Muhammad Khan S/O Ahmed Khan, Muhammad Jawad S/O Muhammad Musa | 163/3 May 16 | 11 | 0 |

| 9. | Tahir Hussain Minhas s/o Khadim Hussain Minhas( Convict no1), Saad Aziz s/o Abdul Aziz Sheikh ( Convict no2), Asad ur Rehman s/o Atique ur Rehman ( Convict no3), Hafiz Nasir s/o Afzal Ahmed ( Convict no4) and Muhammad Azhar Ishrat S/O Ishrat Rasheed Ahmed Convict 5). | 172/12 May 16 | 5 | 0 |

| 10. | Muhammad Qayyum Bacha S/O Mian Said Ghani, Muhammad Asif S/O Anwar Hussain (Convict Number 1), Shahadat Hussain S/O Anwar Hussain (Convict Number 2) and Yasin S/O Muhammad Yar Hussain (Convict Number 3), Muhammad Tayyab S/O Ameer Zada, Said Akbar S/O Liber Khan, Muhammd Ayaz S/O Muhammad Jan, Barkat Ali S/O Abdul Ghaffar, Aziz Ur Rehman S/O Abdul Jalal, Hussan Dar S/O Muhammad Raheem, Ishaq S/O Abdul Hai and Behram Sher S/O Khairan | 242/14 Jul 16 | 12 | 0 |

| 11. | Zia Ul Haq S/O Wali Khan, Fazal e Rabbi S/O Fazal Ghafoor, Muhammad Sher S/O Zaray, Umer Zada S/O Gul Rehman, Latif Ur Rehman S/O Saif Ur Rehman, Muhammad Adil S/O Muhammad Akbar Jan, Israr Ahmed S/O Abdul Rahim Jan, Abdul Majeed S/O Khona Moula, Hazrat Ali S/O Fazal Rabi, Mian Said Azam S/O Mian Said Jaffar and Qaiser Khan S/O Habib Khan | /16 Aug 16 | 11 | 0 |

| 12. | Muhammad Qasim Tori S/O Muhammad Farooq, Abid Ali S/O Muhammad Ramzan and Muhammad Danish S/O Noor Bux, Syed Jehangir Haider S/O Syed Karam Haider and Zeeshan S/O Mureed Abbas and Mutabar Khan S/O Parvanat Khan and Rehman Ud Din S/O Moamber | /22 Sep 16 | 7 | 0 |

| 13. | Muhammad Shahid Omar S/O Zaman Khan, Hussain Shah S/O Fazal-e-Hadi, Zafar Iqbal S/O Muhammad Khan, Anwer Zeb S/O Tootkay, Obaid ur Rehman S/O Fazal Hadi, Sher Alam S/O Hanif ur Rehman, Atta Ullah S/O Muhammad Sultan, Mushtaq Khan S/O Saeed Gul and Asghar Khan S/O Nadar Khan and Shams ul Qamar S/O Sha Gulbar | 357/13 Oct 16 | 10 | 0 |

| 14. | Sajid S/O Ibrahim Khan, Javed Khan S/O Faqeer Gul, Fazl e Haq S/O Shahdad, Fazal Rehman S/O Fazal Karim, Zahid Khan S/O Kitab Shah, Umar Saeed S/O Hazrat Saeed, Rahmat S/O Ismail Khan, Bakht Wali S/O Amal Khan and Nazeer Ahmed S/O Allahdad | 397/7 Nov 16 | 9 | 0 |

| 15. | Hanifa S/O Umar Zareen, Tirah Gul S/O Khan and Muhammad Wali S/O Faulad Khan, Khaista Muhammad S/O Abdul Jalil, (Ali Rehman S/O Habib-Ur-Rehman, Fazal Ali S/O Fazal Wahid and Muhammad Ali S/O Abdul Rehman (RI), Nisar Ali S/O Damsaz Khan, Khial Jan S/O Sayel Jan and Payo Jan S/O Asal Jan | 430/22 Nov 16 | 7 | 3 |

| 16. | Latif Ullah Mehsud S/O Ramzan, Arafat S/O Gul Zarin, Wahid Ali S/O Abdul Ali, Akbar Ali S/O Kareem Ullah, Muhammad Riaz S/O Muhammad Diyar Khan and Noor Ullah S/O Muhammad Diyar Khan, Abdul Rehman S/O Abdul Majeed, Mian Said Raheem S/O Mian Aqal Jan, Noor Muhammad S/O Shah Wali, Sher Ali S/O Mambar, Syed Qasim Shah S/O Syed Amin Shah, Muhammad Usman S/O Khair Ali Khan and Muhammad Waqar Faisal S/O Ghulam Sadiq | 492/16 Dec 16 | 13 | 0 |

| 17. | Hafiz Muhammad Umar alias Jawad S/O Afzal Ahmed, Ali Rehman alias Pano/Tona S/O Asif ur Rehman, Abdul Salam alias Tayyab/Rizwan Azeem S/O Muhammad Nazar ul Islam and Khurram Shafique alias Abdullah Mansoor/Abdullah Mansuri S/O Muhammad Shafiq, Muslim Khan S/O Abdul Rasheed, Muhammad Yousaf S/O Khalid Khan, Saif Ullah S/O Naseeb Hussain, Bilal Mehmood S/O Qari Mehmood Ul Hassan (RI), Sartaj Ali s/o Bakht Afsar (RI) and Fazal e Ghaffar s/o Aqil Khan | 506/28 Dec 16 | 8 | 3 |

| 18. | Riaz Ahmed S/O Ghularam Khan, Hafeez ur Rehman S/O Habib ur Rehman, Muhammad Saleem S/O Muslim Khan and Kifayat Ullah S/O Dilresh | 453/8 Sep 17 | 4 | 23 |

| 19. | Shabbir Ahmed S/O Muhammad Shafique, Umara Khan S/O Ahmed Khan, Tahir Ali S/O Syed Nabi and Aftab ud Din S/O Farrukh Zada | 468/20 Sep 17 | 4 | 0 |

| 20. | Sami ur Rahman S/O Gul Habib and Azeem Khan S/O Shaiber, Arshad Bilal S/O Khadim Khan and Anwar Ali S/O Fazal Ghaffar, Muhammad Aleem S/O Abdull Rasheed and Fazal Aleem S/O Abdul Rasheed, Rasool Muhammad S/O Ahmed Jan, Sohail Ahmed S/O Usman Ali, Naimat Ullah S/O Ahmed and Rahmat Ali S/O Noor Said | 31/19 Jan 18 | 10 | 3 |

| 21. | Atlas Khan S/O Mada Mir Jan and Muhammad Yousaf Khan S/O Mir Azam Khan, Farhan S/O Seen Gul, Khalay Gul S/O Niaz Min Gul and Nazar Moon S/O Akimoon, Nek Maeel Khan S/O Amal Khan and Akbar Ali S/O Bakhtiar | 58/9 Feb 18 | 7 | 5 |

| 22. | Muhammad Ishaq S/O Muhammad Ibrahim and Muhammad Asim S/O Abdul Rehman, Muhammad Arish Khan S/O Muhammad Aslam, Muhammad Rafique S/O Hameed Khan, Habib Ur Rehman S/O Khoba Gul, Muhammad Fayyaz S/O Gul Faraz, Ismail Shah S/O Nek Badshah, Fazal Muhammad S/O Abdul Mateen, Hazrat Ali S/O Muhammad Ali and Habib Ullah S/O Anwar Baig | 131/2 Apr 18 | 10 | 5 |

| 23. | Burhan Uddin S/O Umar Daraz, Shaheer Khan S/O Rehman Uddin and Gul Faraz Khan S/O Wasli Khan, Muhammad Zeb S/O Muhammad Nawab, Saleem S/O Abdul Mateen, Izat Khan S/O Ajib ul Bahar, Muhammad Imran S/O Hazrat Umar, Yousaf Khan S/O Ahmed Jan, Nadir Khan S/O Amir Rehman, Muhammad Arif Ullah Khan S/O Zareen Gul and Bakht Muhammad Khan S/O Ghawas Khan | 162/5 May 18 | 11 | 3 |

| 24. | Ashiq Khan S/O Saad Ullah Khan, Rasheed S/O Momeen Khan, Meraj S/O Sheen Gul, Muhammad Rasool S/O Naikmat Khan, Jannat Karim S/O Gul Karim, Abu Bakar S/O Haider Khan, Anwar Khan S/O Abdul Janan, Ghulam Habib S/O Sher Bahadar, Abdul Ghafoor S/O Muhammad Jan, Rawaz Khan S/O Zameen Khan and Mubarik Zeb S/O Abdul Latif and Ayub Khan S/O Haji Muhammad | 218/2 Jul 18 | 12 | 6 |

| 25. | Ghani Rehman S/O Fazal Rehman, Abdul Ghazi S/O Sabeel Khan, Zia ur Rehman S/O Peer Zada , Javid Khan S/O Noor Zada, Muhammad Zubair S/O Nawab Shah, Umar Nawaz S/O Khaliq ur Rehman, Sajid Khan S/O Sher Rehman, Haibat Khan S/O Nadar Khan, Ahmed Shah S/O Lal Gul, Baz Muhammad S/O Lal Said, Momeen Khan S/O Noor Haleem Shah and Suleman Bahadur S/O Gul Bahadur Khan | 227/13 Jul 18 | 12 | 6 |

| 26. | Khiwal Muhammad S/O Babo Rahman, Saddam Ullah S/O Sher Nawab Khan, Izhar S/O Bakhat Buland, Jan Bacha S/O Bacha Rawan, Sharafat Ali S/O Muhammad Amin, Habibullah S/O Ghulam Ahad, Said Ullah S/O Awal Jan, Zar Muhammad S/O Sakhi Mar Jan, Alif Khan S/O Sardar Khan, Mujahid S/O Yar Wali, Tariq Ali S/O Bawar Shah, Israr Ahmed S/O Taj Muhammad, Kaleem Ullah S/O Hayat Ullah, Muhammad Rehman S/O Sher Ramzan and Fayaz Ullah S/O Muhammad Nawaz Khan | 244/16 Aug 18 | 15 | 6 |

| 27. | Munir Rehman S/O Fazal Rehman, Muhammad Bashir S/O Abdul Rashid, Hafiz Abdullah S/O Muhammad Iqbal, Bakht Ullah Khan S/O Ajmal Khan, Shah Khan S/O Abdul Badshah, Muhammad Sohail Khan S/O Raza Khan, Daud Shah S/O Mian Gul Zada, Muhammad Munir S/O Syed Badshah, Habib Ullah S/O Muhammad Amin, Muhammad Asif S/O Inayat Ur Rehman, Gul Shah S/O Ghuncha Gul, Jalal Hussain S/O Sher Afzal Khan and Ali Sher S/O Rahamdal Khan | 274/10 Sep 18 | 13 | 7 |

| 28. | Rehman Ali S/O Hassan Ghani, Rehmat Ali S/O Sher Malik, Saif ur Rehman S/O Akbar Aman, Fazal Mabood S/O Fazal Rabi, Irshad Ahmed S/O Mumtaz, Afreen S/O Naseem, Ahmad Hussain S/O Qari Muhammad Zarif, Bacha Rehman S/O Masoom Jan, Muhammad Majeed Khan S/O Sanoubar, Muhammad Aqil S/O Nawab Ali, Saif Ullah S/O Muhammad Rafique, Muhammad Sher Ali Khan S/O Sher Afzal Khan, Muhammad Tariq S/O Ghulam Badshah and Ali Rehman S/O Fazal Wahid | 326/26 Oct 18 | 14 | 8 |

| 29. | Anwar Salam S/O Said Nazar, Irfan ul Haq S/O Dilbar, Sahib Zada S/O Akbar Zada, Nadir Khan S/O Ahmed, Izat Khan S/O Bashreen, Imtiaz Ahmed S/O Taj Muhammad, Ameer Zeb S/O Jahangir, Badshah Iraq S/O Muhammad Ishaq, Izhar Ahmed S/O Mukhtiar Ahmed, Akbar Ali S/O Shaiber Sahib and Muhammad Imran S/O Aziz Ur Rehman | 353/23 Nov 18 | 11 | 22 |

| 30. | Hameed Ur Rehman S/O Moazmin Mullah, Said Ali S/O Munawar Khan, Ibrar S/O Abdul Rahim, Fida Hussain S/O Muhammad Hussain, Raza Ullah S/O Ikram Ullah, Rahim Ullah S/O Fateh Khan, Umar Zada S/O Bashar, Amjad Ali S/O Muhammad Ajan, Abdur Rahman S/O Abdul Wahab, Ghulam Rahim S/O Munjra Khan, Muhammad Khan S/O Ghulam Haider, Rahim Ullah S/O Noorani Gul, Rashid Iqbal S/O Hameed Iqbal, Muhammad Ghafar S/O Qari Muhammad Zarif, Rehman Ali S/O Muhammad Aziz | 382/16 Dec 18 | 15 | 20 |

| 31. | Mohi Ud Din S/O Salah Ud Din and Gul Zameen S/O Shah Kameen Khan, Fazal Hadi S/O Bakht Rawan, Muhammad Wahab S/O Hazrat Buland, Gul Muhammad S/O Ghulam Sardar, Bashir Ahmed S/O Nadir Khan, Afreen Khan S/O Masam Khan, Barkat Ali S/O Bakht Hazir, Muhammad Islam S/O Muhammad Zada, Rooh Ul Amin S/O Zarin, Shtamand S/O Baishmand, Bacha Wazir S/O Bakhat Nazir, Mohammad S/O Abdul Shakoor and Muhammad Ismail S/O Ibrahim | 394/21 Dec 18 | 14 | 20 |

| TOTAL: | 310 | 144 | ||

Meanwhile, Shoaib urged for a revamp of the civil judicial system to accept the workings of a military court trial. He highlighted the importance of testimony in cases of terrorism. "The biggest loophole is that the suicide bomber is dead – there are no witnesses. The only people who can link him to the act are found through human intelligence. The agencies find the witnesses and abettors, but their testimonies are rejected by civil courts who ask for further evidence. The convicts claim their confessions were made under duress. The kind of testimony and evidence civil courts seek cannot be provided in terrorism-related cases."

The retired general said the Parliament hid behind accusations of human rights violations to cover their failure to craft an alternate solution.

Masood opined that the government can implement military courts practice of protecting the judges and witnesses identities by using modern technologies. "The judges can perform their duties remotely. The government should make special security arrangements for the judges and prosecutors. It would be in the interest of the justice system to revert back to civil courts as a number of convicts have not been given a fair trial and the decisions have been overturned by the apex court."

Jibran recommended the same procedure.

Gul underscored that the government as a civilian entity and democratic force should not seek an extension of the military courts rather revise existing legal remedies for counter-terrorism. "Reinforce the anti-terrorism courts. At present we have some 52 ATCs – perhaps their number should be increased. They should be provided with strict security – similar to that offered to military courts."

Story by: Hasnaat Malik, Waqas Ahmed, Umer Farooq and Niha Dagia

Produced by: Rahima Sohail

Design: Ibrahim Yahya