LADY HEALTH WORKERS

PAKISTAN'S FRONTLINE CHANGEMAKERS

Community health workers have been pivotal in sustaining trust in modern healthcare the world over. Due to its unique cultural challenges, in Pakistan, the role is entirely based on women.

The novel coronavirus pandemic has not only stretched hospitals across the globe beyond their capacity, but it has also exposed the shortcomings of how different countries manage their healthcare systems.

This particularly holds true for Pakistan where healthcare has long suffered from low funding, lack of governance and dearth of equipment, medical supplies, and staff. For the fifth-most populous country in the world, dealing with large-scale public health emergencies without adequate resources and weak healthcare infrastructure has never been an easy feat.

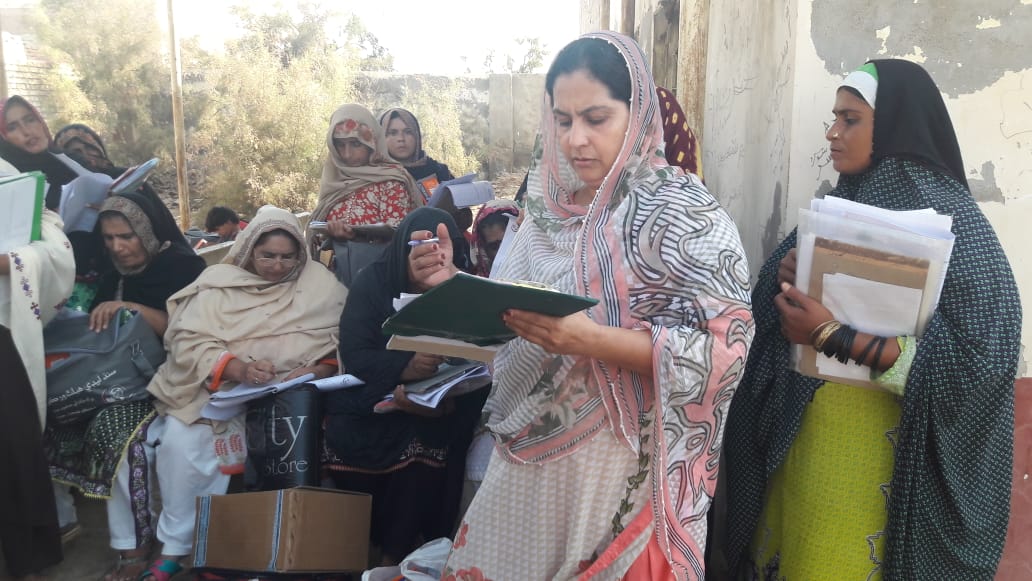

To manage large health campaigns, spread awareness about diseases and epidemics, and assist with the management of health-related crises and disasters, Pakistan largely depends on the services of its Lady Health Workers (LHWs), who provide door-to-door services to impoverished communities in areas that do not have access to comprehensive healthcare.

Why are CHWs so important?

Community health workers (CHWs) have long played a pivotal role in sustaining and enhancing trust in modern healthcare in many countries around the world. A global research endeavour by the independent journalism organisation Orb Media highlights just some of the ways many nations have benefited from CHWs.

Using child mortality statistics as an indicator for the overall health of a community, researchers from Orb gathered and standardised national-level data from 160 countries to identify interesting topics of discussion about child mortality and public health. They also created a statistical model that ascertained the ‘expected’ child mortality rate (CMR) for each country based on their expenditure on formal healthcare structures.

The model showed that between 2010 to 2019, several countries were able to successfully reduce CMR under the age of five without necessarily increasing the number of doctors, nurses, or spending on medical infrastructure. Bangladesh, Honduras, Mexico, Argentina, Thailand, Chile, and Hungary, in particular, stood out in terms of decreasing CMR under five years.

“While each country faced unique barriers and solutions, it was found that all of them, and many other countries surveyed, had deployed community health workers (CHW) as a sound and cost-effective and strategy for community healthcare,” the report read.

According to the research, since CHWs have successfully solved some of the world’s toughest health challenges over the years, they can also help address the most pressing health and equity crises of today’s world, including the Covid-19 pandemic. Besides, CHWs could help boost community trust in local healthcare systems.

Leading with women

In 1994, Pakistan laid the groundwork for its community-focused healthcare delivery by launching the Lady Health Worker Programme (LHWP). With mainstream healthcare dominated by men, traditional attitudes towards women in many Pakistani communities created a barrier in the way of healthcare delivery. By launching a community healthcare initiative based around women workers, the country was able to transcend this barrier, particularly with regards to reproductive health.

Seeing the success of the programme, the government decided to expand the LHWP in 2003 by focusing on the improvement of service qualities and the deployment of 100,000 LHWs across the country over the next two years.

Most LHWs in Pakistan come from moderate to low-income backgrounds. They are attached to a local health facility, but are mainly community-based and work from their homes. Halima Leghari, a LHW from Sindh, joined the programme because she always aspired to become a doctor to save lives. But since she hailed from a conservative, low-income Baloch household, she was unable to pursue a degree in medicine since her family frowned upon the idea of women attending a university.

“When I learned that I could never study medicine and become a doctor, my dreams were shattered. But soon afterwards, the government launched the LHWP, which served as a ray of hope for me,” she recalled. “I intuitively knew that I would be a great fit, but it was not easy to convince my family to let me be a part of the LHWP because I was young and unmarried. Nonetheless, I applied to the programme against all odds. Since then, there has been no looking back for me.”

Leghari has been serving her community as an LHW for the past 26 years and currently serves as a Lady Health Supervisor (LHS). She is also the central president of the All Sindh Lady Health Workers and Employees Union (ASLHWEU).

Akin to Leghari, Rasheeda Baloch, a Lady Health Supervisor from Balochistan, joined the programme 18 years ago with the intention of helping her community. She said that anyone can become an LHW, but they must meet a set of criteria, including a minimum of eight years of education. “We also undergo about 15 months of training, out of which three months are spent in the classroom, while the remaining one year is centred on field-based training,” Baloch explained.

Once the training is completed, LHWs are required to work under the supervision of provincial and district coordinators assigned by the government. “I chose this profession to help the women in my community, who were predominately uneducated and poor. Even though there were many ups and downs, I take pride in my work and am glad to be a part of this noble initiative,” she said.

More than healthcare

CHW programmes can effectively address systemic needs within a community and can include a range of services. According to Orb Media’s research, aside from their regular services, CHWs can provide basic mental healthcare support to community members, can serve as a gateway to healthcare in places which have limited access to clinics, hospitals and medical facilities, educate the masses about health-related issues, and urge them to take preventative measures.

To this end, Pakistan serves as a good example as apart from its focus on maternal and child health (MCH), the scope of LHWs’ services has expanded in keeping with the needs of the communities.

“Aside from advising pregnant women and mothers to take care of their health and referring them to health centres if needed, we mainly monitor and record the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR), the infant mortality rate (IMR), maternal mortality ratio (MMR), skilled birth attendance (SBA), and fully immunised children,” Rasheeda Baloch explained. “We also provide over-the-counter medicines to people for fever, headaches, or other common ailments.”

Since each LHW has access to several hundred households, they are also deployed to carry out large-scale health campaigns. “We actively participate in all vaccination drives, including the polio eradication programme, the dengue and malaria campaigns, community management of tuberculosis, and awareness campaigns on HIV/AIDS,” said Ayesha Hassan, a Lady Health Supervisor from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P), who joined the LHWP in 2004.

Lauding the range of services that LHWs provide, public health expert Dr Naveed Jafri said they serve as the backbone of Pakistan’s healthcare system. “A Lady Health Worker is the only person who is always available on the ground, responding to medical and humanitarian emergencies,” said Dr Jafri, who has been involved in community health and social development programmes for over a couple of decades. “The services of LHWs are also sought whenever there is a natural disaster in Pakistan. This is because each LHW oversees about 150 to 200 households and has in-hand data of all community members, including the number of persons per house, their genders, and ages, among other details.”

Bushra Arain, President and Founder of the All Pakistan Lady Health Worker’s Welfare Association informed The Express Tribune that LHWs are also required to perform some professionally unrelated tasks from time to time. “During elections, we are assigned duties at polling stations and are required to convince women to go and cast their votes,” she said. “We have even performed security duties alongside the police. The LHWs are extremely dedicated, therefore, they never say no to the duties assigned to them and execute them with utmost dedication.”

Trusted intermediaries

Owing to her relentless and dedicated services as an LHW, people of Rasheeda Baloch’s community trust her even more than doctors. “Whenever they are facing some health-related problems or need advice, they come to me,” Baloch said. “Sometimes, they even knock my door at three in the morning, asking for assistance. Even when they return from hospitals, they show me the prescription to ascertain if they have been given the right medicines. This is how much they trust me.”

The findings of Orb Media’s research also showed that CHWs, as trusted members of society, can improve public health by fighting misinformation and disinformation. This is particularly important for areas where people have limited access to television, uninterrupted cellular phone services, and the Internet. “[In such situations], CHWs can act as the main point of contact to provide accurate information related to pandemics, storms, and a variety of issues that can impact health,” the research report read.

“If we are providing our services within our own community, the majority of people trust us and never question our intentions,” Ayesha Hassan said. “However, when our teams are deployed out of station, we often face troubles, especially during the polio campaign. Some people, owing to a lack of education, think that we are foreign agents, and the vaccines are not safe for their children. Since we are not from their communities, it takes time to establish a rapport with them. However, we are fully trained to do it.”

Speaking about the importance of LHWs in establishing communities’ trust in the healthcare system, Dr Amina Khan, Public Health Consultant and Executive Director of The Initiative, a non-governmental organisation focused on public health research and education, said that LHWs are already deeply embedded in the communities, therefore, people trust them.

“They are selected from the communities where they serve and their services are already recognised and appreciated by the community,” Dr Khan said. “The LHWs are the representatives of the local healthcare system, so if we invest in the LHWs and motivate them, the community will benefit.”

She added that the LHWs are the face of the local healthcare system in the eyes of the community they serve, therefore, they can play a crucial role in educating the masses and dispelling rumours and misinformation, including myths related to Covid-19.

A rough journey

Even though LHWs play a crucial role in supporting the country’s healthcare system, they are neither properly compensated for their services, nor receive incentives. As Orb Media has pointed out in its research, the issue of CHW compensation seems to be closely related to a programme’s success and sustainability.

Bushra Arain, who has long fought for the rights of LHWs in Pakistan and mobilised her colleagues from all over the country to stage protests and present their demands in a court of law, said that the journey was far from easy.

“Initially, LHWs were not only poorly compensated for a wide array of services they rendered, but there was no proper service structure available to them, because of which there was rampant exploitation,” she recalled. “It was through various sit-ins, protests, and several court appearances that the government finally regularised our jobs. It took us years, many of our women were arrested, while others retired or died without receiving their rightful compensation. We have recently submitted another petition in the court to pay the outstanding dues to retirees.”

Rabia Begum, another LHW from K-P, said that she and her colleagues even have to perform their duties on weekly and public holidays. “We work from 8 am to 6 pm. Come rain or shine, we have to step out of our houses and visit about 27 houses per week. We are also sent out of station, to far-off areas, without the provision of transportation or fare. In return, the compensation we receive is insufficient. I still perform my duties to the best of my abilities, but for how long can this go on?” she questioned.

In addition to meagre salaries, many LHWs also complained about the risks they have to take to perform their jobs. According to Halima Leghari, when she initially started working as an LHW, people in her community looked down upon her and often resorted to assassinating her character. “We had to endure derogatory remarks, while some of our girls were also subjected to sexual harassment, particularly when they were sent to faraway areas, outside of their communities,” she said.

Similarly, many of them also had to go through physical assaults while performing their duties. “While working on a polio campaign, I received threats to quit the profession. When I did not pay heed, four unidentified assailants opened fire on my car, injuring my son,” Ayesha Hassan said. “Two of our LHWs were killed in broad daylight, only because they were performing their duties. Later, the government provided security to us and now we always go to vulnerable areas accompanied by a guard, but there is always a risk involved. Nonetheless, we never quit our jobs.”

She reiterated that most LHWs feel safe when working within their communities, adding that the problem of vaccine refusals emerged because of the spread of extremism in her province. “There was a time when even uneducated people used to readily vaccinate their kids and opted for family planning, but extremism spoiled many minds,” she said. “The situation, however, has become better as compared to the past. Out of 1,500 houses, we only face 15 to 20 refusals. However, no one is safe even if one child is not administered the polio vaccine.”

The coronavirus challenge

According to Orb Media, during a pandemic, community health workers can also be used as translators, cultural mediators, and healthcare facilitators – traits which are often downplayed. As the number of Covid-19 cases grew in Pakistan, LHWs from all over the country actively participated in coronavirus awareness campaigns.

Nimra Rasheed, who works for the Lady Sanitary Patrol (LSP), a programme that is run by the District Health Authority, Lahore, said that she received coronavirus awareness training in March. “My duties were not only limited to creating awareness, but I was also responsible for collecting nasal swabs from Covid-19 patients and safely take them back to the labs,” she said. “That apart, I was also responsible for providing information to different families about the coronavirus.”

Similarly, Razia Begum from K-P was sent to her regular houses to create awareness about protective measures amid the pandemic. “I provided information about the concept of social distancing, the importance of washing hands and using sanitisers, and wearing a mask,” she said. “Ninety-nine per cent of the families I visited carefully listened to the instructions and asked pertinent questions for their safety. I also discussed the possible introduction of a Covid-19 vaccine in the coming year to mentally prepare the members of my community.”

Even though LHWs sincerely performed their duties during the Covid-19 campaign, Halima, Razia, and Bushra complained of receiving limited or no PPEs and sanitisers to protect themselves. “I was just given a 50 ml sanitiser bottle. Many of us had to spend out of our own pockets to keep ourselves safe from the potentially deadly disease. If they deployed us, they should have taken care of us too,” Halima said.

Dr Jafri shared similar concerns about the safety of LHWs. Owing to their familiarity with the members of the community, LHWs have also played an especially important role in Covid-19 contact tracing, a practice used by health departments to prevent the spread of infectious diseases by identifying people who came in close contact with infected patients.

“They diligently performed their jobs and can help in pandemic preparedness in future too, but there is a need to strengthen such awareness campaign by ensuring that workers are given adequate supplies of PPEs so that they can perform their jobs more reliably,” he said.

Dr Amina Khan opined that it is an obvious choice for the government to utilise the services of LHWs amid the pandemic as this is the only organised outreach (door-to-door) system in Pakistan which has proven to be effective. “If properly trained and compensated, the LHWs will further prove to be an asset and can bring about great results,” she said. “But it must be remembered that there is a fine line between utilising and misusing their services. We need to motivate them and compensate them fairly.”

On the other hand, Dr Fareeha Irfan, a medical doctor and health policy and management expert from Punjab, said that LHWs can help with Covid-19, but it is important to remember that they already have predefined jobs.

“Diverting that trained workforce toward a new, widespread problem would affect their existing work. While it makes sense to use them as the first line of defence, it is important to have the ability and capacity to hire additional workforce for this task so that LHWs can effectively focus on their original duties,” she opined.

She added that the same is true for their role in any pandemic preparedness planning. Their expertise in health communication and door-to-door service is a valuable asset on which any future pandemic planning (including vaccination, once it is available) should count on, but it’s important to continue routine preventive work which would not disrupt the important work that LHWs are doing.

“If additional tasks, such as Covid-19 related work, are assigned to LHWs, that is fine but it should never be at the cost of their original duties.”

Story: Sarah B Haider

Story in collaboration with ORB Media Network

Produced by: Niha Dagia, Zeeshan Ahmad & Hammad Sarfraz

Illustrations: ORB Media Network

Photos: EXPRESS