Afraid of societal stigma, victims and their families often hush up cases of revenge porn, online harrassment

Karachi: With a chador wrapped around her head and face, a scared and jittery young woman sat in the waiting area of the Federal Investigation Agency’s Cybercrime Circle in Karachi. Next to her was an elderly woman, like a deer caught in the headlights, waiting to speak to an investigation officer.

Every now and then, the older woman whispered something to the girl, and went redder in the face in the process. Tears welled up in the young woman’s eyes. Try as she would, the tissues were not enough to soak up her tears as they streamed down behind the chador.

As she fidgeted with the tissue, an official announced: “The officer is calling Miss F”

The two women got up with their handbags and headed into the investigation officer’s room. The older woman introduced herself as F's aunt and began narrating the ordeal her niece and whole family were facing.

A student at an all girls college, F met Z at an inter-collegiate sports event three years ago. It was like any other such liaison between teenagers, growing from clandestine calls into surreptitious meetings. There were a few video calls in between and exchange of photographs, but F insists it was all above-board.

As the relationship grew, she found out about Z other activities, which included petty crime and even a prison term. He also disappeared for long stretches, which for F was another red flag. Alarmed at these developments, she tried to put distance between the two.

That’s when things started to go wrong. Angry at being spurned, he started with threats against F and her family. Initially, she brushed off his advances as idle threats, but when he repeatedly threatened to send compromising images of her to her family, she knew there was trouble.

She confided in her aunt, scared as she was of causing irreparable damage to her relationship with her father. At that time, her family was busy with the marriage of her elder sister, and appeased Z through whatever means necessary.

But that didn’t last long. Early last year, F woke up to find her intimate pictures displayed over multiple social media platforms. They were also sent to her family members. Soon, everyone in her extended circle had seen the pictures, with her pleas to Z to take them off falling on deaf ears.

Driven to despair, she tried to kill herself, not once but twice, saved by timely intervention of her family. They convinced her to take up the case with the relevant authorities but the shame associated with the offence continued to be a deterrent. She was still sticking to the hope that her intimate images would be lost in the multitudinous oblivion of cyberspace.

However, the situation kept spiraling out of control. Things came to a pass early this year when Z decided to accuse F of blasphemy.

The amplification in threats directed at her and her family meant that there was no way out but to cooperate fully with the authorities. F was back at the cybercrime office in Karachi, and this time she was determined to get all questionable content associated with her removed from social media.

'One of dozens'

FIA Cybercrime Circle Deputy Director Abdul Ghaffar says that F’s case is not just an isolated incident and his department receives dozens of such complaints on a daily basis. “The number of reported cases have risen recently and the majority are about harassment on WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook.

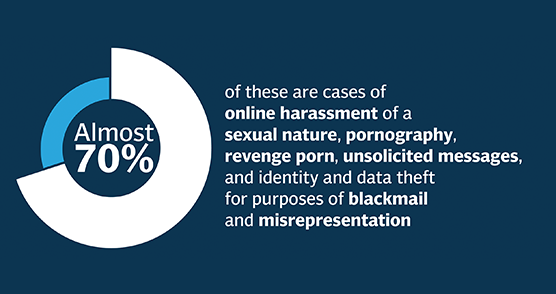

He said that last year FIA received more than 4,000 complaints regarding cybercrime, while more than 1,500 complainants have been received in the first three months of 2019. “Of these, almost 70% of the cases are related to online harassment of a sexual nature, pornography, revenge porn, unsolicited messages, and identity and data theft for purposes of blackmail and misrepresentation.

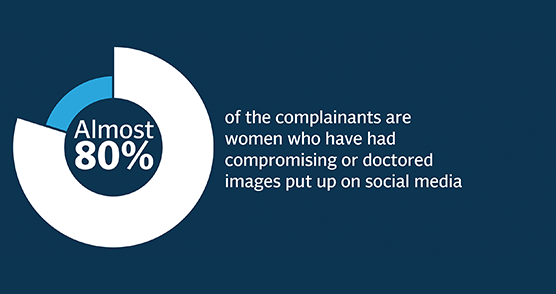

“In cases, the majority of the complainants, almost 80 per cent, tend to be women, who have had compromising or doctored images put up on social media. In the majority of cases, the person who put up the picture is known to the victim,” he informed.

Hush it up

When asked whether she sought criminal action against Z, F told The Express Tribune that she wants to move on and focus on her education and family instead of worrying about what she will find out next on social media.

She is still reluctant about taking the issue to court. “I know I made a mistake by trusting him. I just want to make sure that I don’t have to hear from or see him ever again in my life. He has ruined it enough already. I don’t care how the authorities to deal with him.”

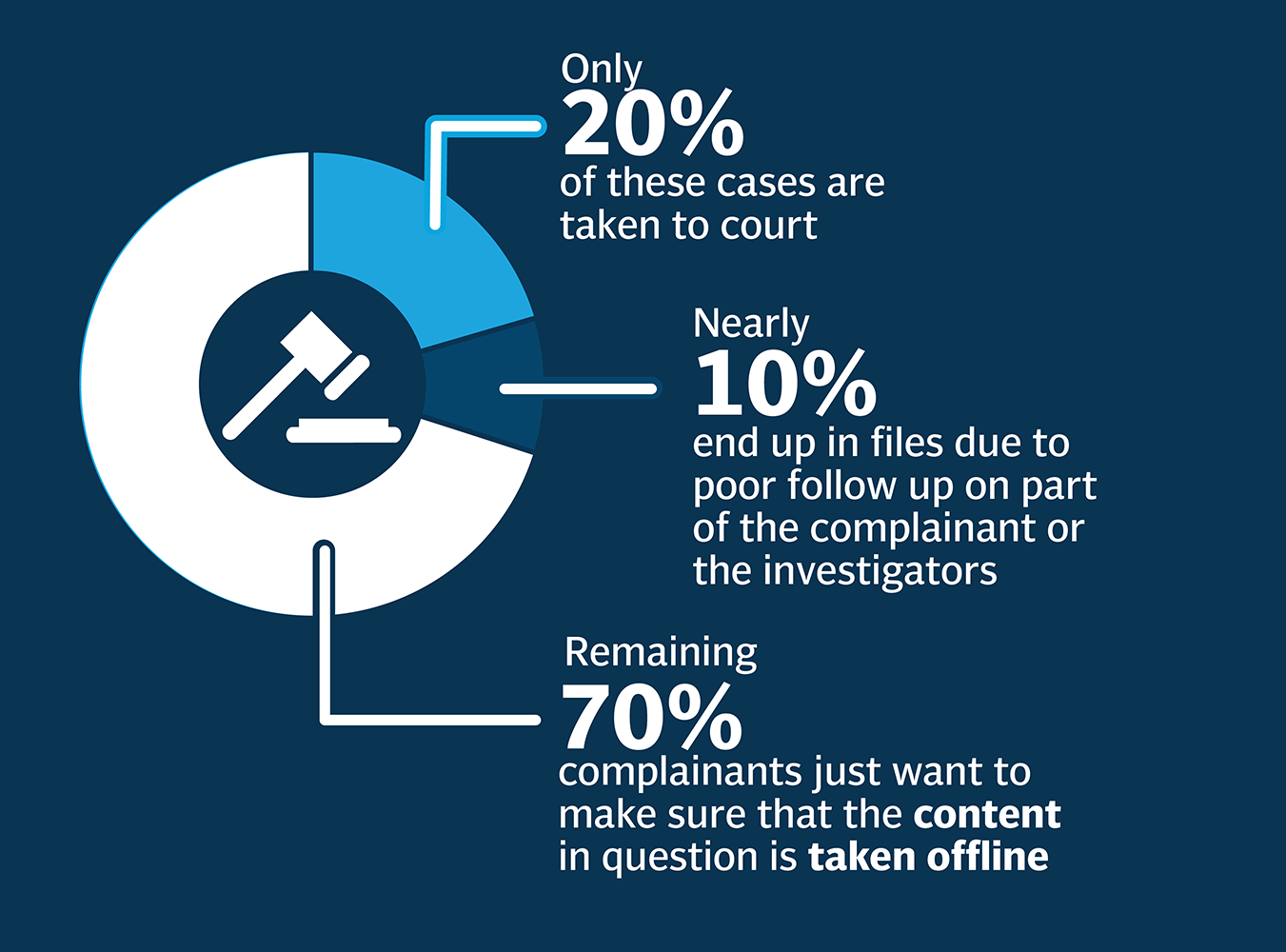

Ghaffar said that F’s case is expected to follow the same trajectory as do the majority of cases. “Only 20% of cases are taken to court. Nearly 10% end up in the files due to poor follow up on part of the complainant or the investigators. In the remaining 70%, complainants just want to make sure that the content in question is taken offline.”

He went on to say that complainants and their families are unwilling to take the matter to court due to its sensitive nature. “People are concerned about further damage to their reputation. They don’t want their names or images to be part of the court record. They don’t want to be known. All they want to ensure is that they do not have to deal with the individual ever again, and understandably so.

Repeat offenders

While the victim is satisfied by the removal of the objectionable content and an unconditional apology, it limits the agency’s ability to try the perpetrator through the legal system is compromised. This means that they have to let the perpetrator go, despite knowing their proclivities.

Investigation officer Tariq Hussain, who is an IT expert, cited the case of a man who impersonated as an army officer and duped women with promises of marriage. The man hired a fake molvi to carry out the nikkah to sanctify the consummation of marriage. He also recorded the act of consummation, which he then used to blackmail.

“We arrested the man a few years ago, but had to let him go after the victim agreed not to press charges as the content was removed and the blackmailing ended. Last year, there was a complaint about another man impersonating as an army officer. When we tracked him down, it was the same man,” narrated Hussain.

He said that his investigation revealed that the perpetrator had carried out the same scam with at least four different women that they know of. “We don’t know how many other women he duped. But now, one of the victims has agreed to go ahead with the case and it is now in court,” said Hussain, while acknowledging that the cases could have been avoided if they had been able to take action earlier.

Paucity of resources

One of the challenges facing the cybercrime wing is a dearth of resources. The resources have not grown apace with the rising number of complaints that they have to handle since the setting up of the wing in 2007. The passage of the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Ordinance (PECA) in 2016 resulted in greater focus on the wing’s activities but without the necessary addition to resources.

At present, Pakistan has around 35 million active social media users, according to a Global Digital report prepared by We Are Social and Hootsuite. Meanwhile, a Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) report stated that cellular subscribers in Pakistan crossed the 150 million mark in June last year, with over 10 million new subscribers added in the 12 month period preceding it.

One investigation officer, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that the Karachi office has two technical experts and one forensic expert to deal with the cases. “The experts were hired ten years ago. They don’t receive refresher courses. There is so much changing and we need to know about it in order to better handle the situation,” the officer said.

The officer also underscored the importance of having investigators trained in interviewing complainants who are often young women who are vulnerable and dealing with conflicting pressures from the family and the society.

Deputy Director Abdul Ghaffar, whose intervention was pivotal in the F case, says the greatest challenge facing the agency is a lack of agreement with social media websites. “Currently, it takes almost three weeks to get Facebook to remove objectionable content. That’s light years in the internet world. We need policymaking at the highest level to come to agreements with these social media behemoths to drastically reduce the time in order for our actions to be more effective.”

Crusade in the digital age

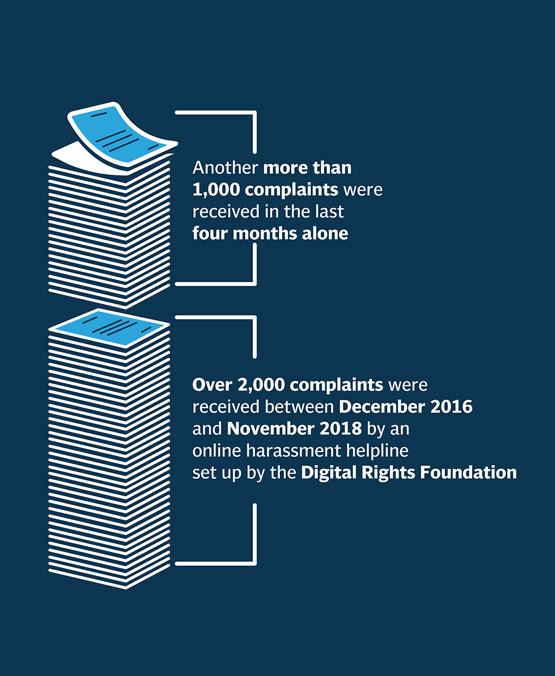

Nighat Dad runs the Digital Rights Foundation, which focuses on digital security and online harassment among young women. She set up an online harassment helpline in December 2016, and it received over 2,000 complaints in the first two years till November 2018.

However, the last four months have witnessed a sudden upsurge, with over a 1,000 complaints, says Dad, adding that the complaints are not just limited to the digital space but also the work place as well as those on WhatsApp. The DRF has since set up another helpline, and enlisted lawyers willing to provide their services on pro bono basis. It also refers complaints to relevant authorities, including the FIA, as well as following up on them.

It has also successfully approached major social media websites to take down content including ‘intimate images shared without the consent of the individual’ or those that places an individual’s life in danger. The efforts have borne fruit as Facebook recently set up pre-emptive mechanisms, in consultation with experts from five countries including Pakistan, to detect and block the uploading of such images.

Dad also criticised victim blaming, often the knee-jerk response in such cases, and underscored the importance of understanding consent, where sharing an intimate image with one individual doesn’t mean that that individual has the right to share that image with others.

The names in the story have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Reporting: Adil Jawad and Hussain Dada

Creative: Ibrahim Yahya