Valley of death

Living in the Indian army’s crosshairs

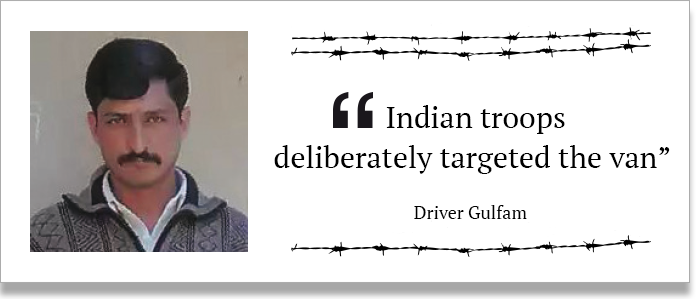

It was a cold, quiet November morning of 2016. A van carrying over a dozen villagers was cruising past the sleepy village of Nagdar Kinari on a road snaking through the lush mountains of the scenic Neelum Valley along the Line of Control (LoC) in Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK). The vehicle was headed to state capital Muzaffarabad.

Across barbed wire, Indian troops could easily tell this wasn’t a military vehicle. And with their field glasses, they could even see the faces of passengers in all probability. Suddenly, the melodic silence of the picturesque village was shattered. A rockets blitz whistled through the cold air. Boom, boom, boom! The Indian troops were shelling madly. A mortar shell tore into the van and tossed it off the road. They didn’t hold fire. Shells rained like hail. Shrapnel whizzed all around. An unending crackle of machinegun fire followed. An ambulance came to evacuate the casualties. The vehicle was not spared either. Perhaps the Indians wanted to make sure no one was rescued. By the time the injured villagers were driven to hospital, nine had already died – another seven were fighting for life.

Survivor: Soldiers shifting a man injured in the November 2016 Indian attack on a passenger van

India couldn’t justify such unprovoked violence. So, it went into denial. Brazen and unabashed denial! It got away with what, according to international law experts, clearly constituted a blatant violation of the Geneva Conventions which seek to protect people not taking part in hostilities.

The Pakistani electronic media stirred up ritualistic jingoism by whipping up an anti-India frenzy over a couple of days. A token diplomatic protest was also lodged. And then the incident was consigned to history. Nine innocent lives were snuffed out. Nine families were left bereaved. It was the biggest loss of civilian lives in a single episode of Indian shelling. The tragedy went unnoticed internationally. No condemnations came through. Nothing! An unsympathetic silence!

Sitting ducks

Troops on both sides of the LoC are relatively secure in fortified concrete bunkers but civilians are like sitting ducks. And Indian troops realised if they couldn’t hit enemy troops, they could easily kill civilians and get away with it. A year later, they did it again. This time they targeted a van carrying schoolgirls in Dharamsal village of Battal sector on February 15, 2018. An Indian sniper fatally shot Umar, the driver of the vehicle. Luckily, the van lumbered into the roadside barrier and halted. The schoolgirls remained unharmed, though terrorised to death. Three days later, an Indian sniper shot eight-year-old Ayan Zahid as he played outside his house in Jijot village of Kotli sector. On February 22, 19-year-old Inzemam Amin, a resident of Tetrinote village, was killed by an Indian sniper as he worked at a stone crushing plant in Battal sector.

Such wanton violence, methodical killing of civilians is a norm for Indian troops, according to residents of Battal and Mandhol villages lying on the banks of the River Poonch. “They routinely shell our village,” says Muhammad Umar, a resident of Battal village, who himself was injured in Indian shelling. The two villages, with a population of nearly 5,000, have faced umpteen Indian onslaughts. Walls of every second house are pockmarked by bullets or torn off by shells. Every family has a story to narrate. Dugouts and makeshift bunkers speak much about life in these villagers living right in the Indian crosshairs.

A house in Battal Sector with bullet holes in the wall

The blame game

Pakistan and India share a 3,252-kilometre-long border. Part of it, 2,175 kilometres to be precise, is internationally recognised. The rest is divided into the Line of Actual Contact (LoAC), 108 kilometres; the Line of Control (LoC), 767 kilometres; and the Working Boundary (WB), 202 kilometres.

Troops from the two countries have been eyeball to eyeball since 1948. In 2003, the two sides agreed to a ceasefire. Interestingly, the truce was unilaterally offered by Pakistan’s then prime minister Zafarullah Jamali. It’s a verbal understanding, and not a written agreement. The truce has been holding since, though both sides routinely accuse each other of violations. Efforts were made under the Composite Dialogue Process to formalise the understanding but fell through after New Delhi called off talks accusing Islamabad of harbouring militant groups carrying out attacks in India.

The recent flare-up along the LoC and the WB, the worst since 2003, started towards the second half of 2016 after 17 Indian servicemen were killed in a militant attack on a military base in the Uri area of Indian Occupied Kashmir (IOK) in September that year. India blamed the deadly assault on the Jaish-e-Muhammad militant group which it claims operates from Pakistani soil. The attack came at a time when IOK simmered with anger in the wake of Burhan Wani’s killing. Wani was the poster boy of IOK’s indigenous armed struggle against the Indian rule. This, India found convenient to ignore.

According to a military tally, at least 44 civilians, among them women and children, have been killed in over 2,000 ceasefire violations by Indian forces since 2016. Another 154, also civilians, have been wounded. International law experts say targeting civilians constitutes a blatant violation of the Geneva Conventions.

Troops from both sides point accusatory fingers at one another. “I can say with certainty that Pakistani troops do not initiate fire,” says a senior security official deployed at the LoC. “And I’m sure Indian troops privately admit that. They would never say so publicly though.”

According to defence analysts, Pakistan cannot afford to initiate hostilities with India on the LoC for many reasons. Firstly, the Pakistani military stands stretched thin. A huge deployment of troops on western border is busy fighting Taliban terrorists sneaking in and out of Afghanistan. The finest army officers are also deployed there. India has three times more troops deployed along the LoC than Pakistan. Secondly, Pakistan would never jeopardise a popular indigenous uprising against the Indian rule in IOK by escalating tensions along the LoC. Furthermore, Pakistani troops would never endanger lives of civilians dwelling along the LoC by initiating fire knowing it would be retaliated.

Indian forces say they fire only to stop infiltration. The claim holds no ground. “The de facto abrogation of the ceasefire agreement by India took place in second half of 2016, which means the so-called infiltration took place in the years before,” a senior security official says. “But interestingly, until the second half of 2016 the Indian military claimed that so-called infiltration had substantially declined.”

In a January 2016 media talk, the then Indian Army Chinar Corps GOC Lt Gen Satish Dua said infiltration from across the LoC was “down to a trickle” because of the “counter-infiltration grid and alertness of Indian troops”. Moreover, the Indian military has erected a fence along most of the LoC, and mapped ‘probable routes of infiltration’ where round-the-clock vigilance is maintained by troops equipped with ground sensors, thermal imagers and battlefield surveillance radars. “It is impossible for infiltrating militants to cross over the three-tiered border fencing along the LoC,” Brigadier A Sengupta, who commanded the front brigade deployed to guard the LoC in forward sectors, said in a 2014 interview. Tellingly, Indian website South Asia Terrorism Portal which kept track of so-called infiltration attempts into IOK in addition to incidents of terrorism has been taken off.

India's three-tiered security along LOC

AJK has literally remained unscathed by the wave of terrorism sweeping across Pakistan. “This shows that the Kashmiris are a peace-loving people. The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan tried to open a franchise in AJK, but it couldn’t last (even) two months. The Islamic State, too, failed to gain a foothold in the region,” says AJK Education Minister Iftikhar Gilani. “Given their peace-loving nature, how could Kashmiris allow their soil to be used for violence and terrorism?”

Indian designs

Why does the Indian army seek to escalate tensions along the LoC? And why does it target civilians? Does it have specific objectives?

Yes, say Pakistani officials. New Delhi wants to divert international attention from what it has been perpetrating in IOK, according Gilani. India wants to distract attention from blatant rights abuses and use of brute force to quell the freedom struggle underway there. “New Delhi also wants to scare the civilian population away from the areas along the LoC to facilitate its conversion into a permanent border,” adds a security official.

But Kashmiris say the Indians cannot scare them out of their villages. “India can never break the will of Kashmiris. They will never abandon their villages and relocate,” adds Chaudhry Muhammad Yaseen, the opposition leader in the AJK Legislative Assembly.

.

If neither side concedes violations, then who decides which side is at fault? The United Nations Military Observers Group on India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was constituted under a 1949 Security Council resolution to supervise the ceasefire. India, which claims the erstwhile princely state in full, has long bristled against any external involvement in the disputed region. New Delhi argues the UN has little role to play after the 1972 Simla Agreement. This is precisely why India wants the UNMOGIP out of the region. In 2014, observers were ordered to vacate a government-provided bungalow in New Delhi. Pakistan, on the contrary, facilitates UN military observers. The group has provided little help when it comes to fixing responsibility for ceasefire violations.

In a situation like this, what option does Pakistan have to stop India from attacking Kashmiri civilians? Lawyer Farogh Nasim says Islamabad can take up the matter at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or the UN Security Council. “If Pakistan has solid evidence, the ICJ could pass a ruling against India,” says Nasim, who holds an LLM from the London School of Economics and a PhD in comparative constitutional law from University of London. “And if Pakistan goes for the second option, the Security Council could appoint an arbitrator to examine the situation and present its findings before the relevant committee.”

Meanwhile, the tally of Kashmiri civilians killed by unprovoked Indian aggression looks set to rise as the comity of nations maintains a callous silence.

The human cost

Chapter 1

They do not even spare livestock

Verdant greenery, towering peaks and the clear waters of the River Poonch make Rawalakot’s Battal one of the most stunning areas in Azad Jammu and Kashmir. But, its beauty is not without blemish. Situated on the Line of Control (LoC), the area is routinely subjected to unprovoked Indian aggression. Bullet-ridden walls, cratered roofs, damaged courtyards and livestock pens all stand testament to deliberate Indian attempts at striking fear in civilians’ hearts.

Resident Muhammad Adeel lost an eye after being injured in cross-border fire. “I was at home when the firing started. I was taken to Rawalpindi’s Combined Military Hospital (CMH) where doctors operated on my left eye and jaw. Some of my teeth were removed too,” he said.

“Now, I see with only one eye. I have lost half my teeth. I urge global rights organisations to take note of violence perpetrated by Indian forces across the LoC. Can the world give me my eye and teeth back,” he bemoans. The man said he was indebted to the Pakistan Army for quickly shifting him to the CMH Rawalpindi and ensuring the provision of quality healthcare.

A resident of Battal who lost an eye after being injured in cross-border fire

Mahmood Naqvi, another Battal resident, said it pained him greatly to see his damaged house. This, he said, was the price exacted for electing to stay where their ancestors dwelled before them. “Our house was shelled by Indian forces in November, 2016. The entire building is pocked-marked by bullets. My wife, who was at home, was injured in the episode. The men were out and the children at school. Words fail to do justice to the pain we continue to endure,” he added.

The roof of a house damaged as a result of Indian shelling

Naqvi said the Indian army does not even spare livestock. “We have lost buffaloes, cows, sheep and goats. It is unfortunate that animal rights organisations never take this up,” he added.

Farmer Mahmood Hussain said Battal, Dharamsal and Mandhol residents had lost over 100 cattle to Indian fire in November 2016. He said the livelihood of many Battal residents rested on selling milk. Hussain said Indian antics had left many without a source of income. “The Indian army has wreaked havoc on our lives,” he said.

Cattle in Battal Sector killed as a result of Indian firing

Another farmer Abdur Rahim has lost two buffaloes, five goats and an ox since 2016. “They were the only assets I possessed. I wonder what they have been ‘punished’ for! Even dogs are not spared,” he said.

Schoolchildren and civilian transport are often targeted too. The Battal resident said those living along the LoC suffered the most. He said they were the most prominent victims of Indian “state-sponsored terrorism”. Naqvi said the international community should take action against India for stoking tension along the LoC in a deliberate attempt to compromise regional peace.

Vehicle damaged after cross-border fire

Chapter 2

AJK young brave bullets for books

Incessant ceasefire violations along the Line of Control (LoC) in Azad Jammu and Kashmir’s Battal area have left schoolchildren terrorised. Locals say the Indian army routinely targets schools along the LoC. A 2016 attack on the Government Girls High School in Battal left two buildings destroyed in its wake.

“We rush children to the basement whenever the LoC flares up. Gone are the days when sound of gunfire used to frighten us. Now, it is not uncommon to hear fire being exchanged during school hours. The Indians want to strike fear,” Mahnoor, a teacher at the school, said.

She said it was hard to foster a conducive environment in damaged buildings. Mahnoor said teachers encouraged students by reiterating the importance of knowledge as the sole way of overcoming adversity. She said ensuring students remained in the right frame of mind presented yet another challenge.

Yasra, a grade five student, was left without a leg after being hit by mortar fire. I was reading when that happened, the child said. She was later taken to Rawalpindi’s Combined Military Hospital (CMH) where she underwent an amputation procedure. “I’ll never be able to forget. There was blood everywhere,” Yasra said.

Why civilian installations and non-combatants are targeted is all she wants to ask Indian forces. Yasra said the international community should influence India into stopping this. “After all, we are human too,” she said.

Youngest victims: Little Yasra was left without a leg after being hit by Indian mortar fire

Another student, 10-year-old Muhammad Omer, was studying at home when gunshot from an Indian post left him injured. “I remember hearing gunfire and falling down. I was brought to Rawalakot’s Shaikh Kahlifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan Hospital. My parents said I had received a bullet in the neck,” he said.

The grade four student said he could not fathom why the Indian army would target a child studying at home. He said his academics suffered too as he was not able to go to school for months. “It affected my parents and peers too,” Omer said.

10-year-old Muhammad Omer, was studying at home when gunshot from an Indian post left him injured

Additional reporting by: MA Mir and Hasnaat Malik

Produced by: Shaheryar Popalzai

Photos by: MA Mir and AFP

Design: Ibrahim Yahya and Saadat Ali

Copyright © 2018 The Express Tribune